You Kant Get There from Here

The second in a series . . .

In my last essay on “Truth, Nihilism, and the American Founding,” I examined what I consider to be the most powerful philosophic critique of the classical-liberal tradition and the principles of the Declaration of Independence. That critique—in the form of historicism, relativism, and nihilism—involves at its core a rejection of the concept “truth,” which served as the metaphysical and epistemological foundation of the old liberalism. At the deepest philosophic level, this is where the most important battle is. One cannot champion the moral principles of the founders’ liberalism without first understanding and defending the concept “truth.” The philosophic principles of classical liberalism must be upheld first and foremost because they are true in theory and in practice and only secondarily because they work or have salutary consequences.

Before we start shoring up the foundation of America’s original system of government with stronger philosophic materials, we must first better understand the internal weaknesses, flaws, and contradictions that led to its demise. The eventual decline and fall of the Declaration of Independence was not simply or solely due to relentless and overwhelming philosophic opposition. America was history’s first philosophic nation, but the truth of the matter is that its original political foundation was built with borrowed and sometimes deficient philosophical materials that later proved inadequate to the task of defending America from its future philosophic critics. This is a sad but important truth. This essay examines the philosophic antecedents that contributed to the downfall of the founders’ liberalism.

The Founders’ Hopes and Aspirations

America’s founding fathers were men of action and brilliant philosophic statesmen, but they were not philosophers. It was not their responsibility during wartime and the founding of a new nation to establish a comprehensive and consistent philosophic system on which to ground their political and constitutional principles. Like most enlightened people of that enlightened age, America’s founders assumed they were building a new nation on the basis of certain self-evident truths that had been revealed for all to see by Europe’s great philosophic innovators. They were tragically mistaken. The principles on which they founded this nation were not and are not self-evident. True enlightenment is not quite so simple.

The fundamental problem is that the founding fathers mistakenly took for granted that the philosophic foundation of their core principles and institutions had been established and properly defended by their philosophic teachers. The founders universally accepted the Enlightenment view that reason was man’s only means of acquiring genuine knowledge, which meant that the liberation of man’s reason from faith, revelation, mystic insight, and monkish ignorance would open up new vistas of human knowledge.

Thomas Jefferson’s famous letter to Roger C. Weightman, written two weeks before the Virginian passed, summed up all of the hopes and aspirations of the Enlightenment and the Declaration of Independence:

May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all), the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. That form which we have substituted, restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God. These are grounds of hope for others.

In this one brief passage, Jefferson connects the necessary dots between reason, truth, science, freedom, and rights. This is the vision and meaning of Enlightenment liberalism.

The Enlightenment Ur-text that began to sweep away centuries of dogmatic mysticism was John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). Locke’s negative purpose was to remove “some of the rubbish that lies in the way of knowledge,” and his positive purpose was to “inquire into the original, certainty, and extent of human knowledge, together with the grounds and degrees of belief, opinion, and assent.” In other words, he sought to determine what men can and cannot know, particularly as it relates to man’s moral conduct. This was the great ambition of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, and America’s founding fathers sought to put the Enlightenment ideals into practice.

Jefferson represented the founding generation’s confidence in the power of reason to unveil nature’s hidden secrets. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson advanced one of the clearest Enlightenment statements on the power and efficacy of reason: “Reason and free inquiry are the only effectual agents against error. . . . They are the natural enemies of error, and of error only. . . . Reason and experiment have been indulged, and error has fled before them. Truth can stand by itself.” Unassisted human reason was for Jefferson the only means by which to discern the laws of nature, including the moral laws of nature. In a 1787 letter to his nephew, Peter Carr, Jefferson advised the young man to “fix reason firmly in her seat and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of God; because, if there is one, he must more approve of the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.” The revolutionary generation all believed that reason can distinguish between just and unjust, good and bad, freedom and tyranny.

But almost from the beginning there was a problem. At the very moment when Jefferson and America’s founding fathers were announcing the triumph of reason in the New World, the Old Word was announcing its premature death.

From Skepticism to Mysticism

The founders’ claim for reason was assumed and asserted but not properly understood, explained, or validated. Jefferson and his fellow revolutionaries assumed that John Locke and other Enlightenment philosophers had made an irrefutable case for reason and its power, at least relative to the proponents of mystic faith and revelation. They were mistaken. Locke was no doubt a proponent of reason and he went further than any philosopher since Aristotle in defending it, but it is also true to say that his understanding of what reason is and how it works was deeply flawed.

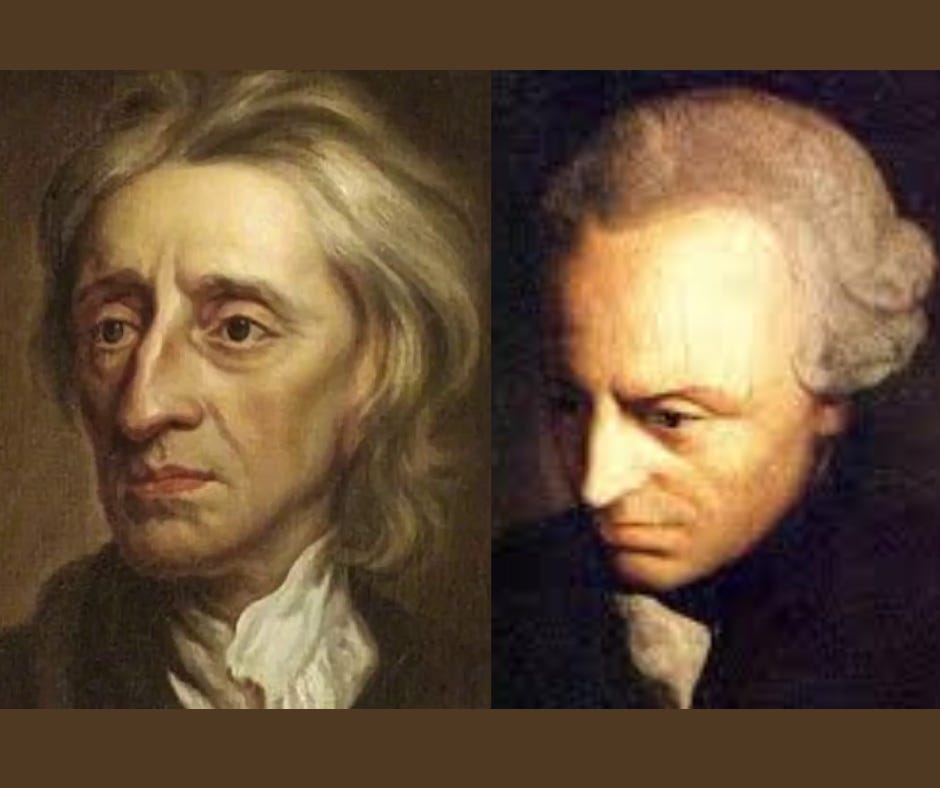

Despite his best efforts, Locke was not able to establish the validity of the senses and their precise relationship to man’s reason, validate rationally the reality of nature, or prove the nature and reality of causality—all of which are necessary to establish the potency of reason and to establish discovered knowledge as objectively true, certain, and absolute. In the end, the best that Locke could do was to establish a system of knowledge that was probably or partially true rather than demonstrably and absolutely true. In the end, Locke’s failure opened the door to skepticism (which means doubt) and in walked David Hume and Immanuel Kant.

Within a century, Locke’s Enlightenment project was in tatters. The Scottish philosopher David Hume, for instance, directly challenged Locke’s claim that reason (via the senses) could produce certain knowledge of entities and the causes of their action or movement. In other words, the law of causality or cause-and-effect relationships could not, according to Hume, be known or explained. No matter how many times an observer sees a cause-and-effect relationship (e.g., the movement of a billiard ball), he can never know with logical certainty or absolute confidence that the same cause will lead to the same result in the future. This meant that men could have impressions of things in the here and now and opinions about them but no true or objective knowledge of the world. Hume did not think that reason alone was capable of discovering, identifying, knowing, declaring, and affirming a truth about the ultimate nature of things.

It was Immanuel Kant, though, who, more than any philosopher, put the final nail in the coffin of the Enlightenment’s hopes and aspirations to achieve objectively verifiable knowledge of reality. In his major treatise, Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), Kant launched a philosophic assault against the Enlightenment understanding of reason, nature, objectivity, knowledge, and truth.

Aroused from his “dogmatic slumber” by Hume’s enervating skepticism, Kant concluded that man could only partially or imperfectly know concrete entities (i.e., the appearances of various “phenomena”) or discrete events via sensory experience. Moreover, in a post-Humean world, Kant did not think that man could know the causal connection between events (e.g., the rising sun). Man could never have certain knowledge of “true” reality (i.e., what called the “noumenal” world); he could never truly know via reason the existence of non-empirical things, such as “God, freedom, and immortality.” In other words, you Kant get there from here!

To wiggle his way out of this conundrum, the professor from Königsberg launched what he called his “Copernican Revolution,” which recentered—in many ways it actually reversed—the Copernican relationship between man (subject) and nature (object). For Kant, the nature of the human mind and its relationship with reality is such that the sensory data received by the mind is channeled and processed by twelve innate categories hardwired in the mind (e.g., space, time, substance, quantity, relation, causation). Nature and the knowledge of it are not, according to Kant, independent of the mind. In Kant’s cognitive universe, the reality of nature is actually presumed by and built into man’s cognitive software. In the act of acquiring knowledge and understanding the world, human reason does not conform to reality; instead, reality conforms to the categories of man’s mind. In Kant’s words, “the object (as object of the senses) must conform to the constitution of our faculty of intuition,” which means that reason cannot truly know anything outside itself. In other words, human cognition shapes reality and is therefore the center of the universe.

It was Kant, then, who killed the Enlightenment by unleashing radical subjectivism on the world. Knowledge of the world is projected or created rather than discovered. Thus, it was Kant who destroyed the possibility of discovering the “truth”—objective truth—about nature and man’s relation to it—truth as absolute, certain, universal, and permanent—truth as defined by Noah Webster as that which is in “conformity to fact or reality; exact accordance with that which is, or has been, or shall be.” For Kant, “truth” signifies the consistency between internally generated ideas. To be clear: this is not a “Copernican revolution” for human knowledge; it is the anti-Copernican revolution!

Thus, Immanuel Kant was the prime mover in launching the nineteenth-century revolt against reason and objectivity. He reversed and destroyed man’s necessary and proper relationship to reality. It was Kant who held that man’s mind was incapable of acquiring genuine knowledge and hence the truth about the real world. It was Kant who claimed that man’s mind via reason, logic, and science was cut off from penetrating to and knowing true reality. It was Kant who said that men could only know the surface (“phenomenal”) world of appearances rather than the true (i.e., “noumenal”) world “as it is.” It was Kant who said that the objects which men experience must conform to their pre-established knowledge or what they “put into them.” It was Kant who ushered in the age of subjectivism by claiming that the human mind is pre-programmed to filter automatically the information that it receives from the five senses. It was Kant who claimed that man’s mind generates or creates the nature of existence without actually knowing it as it truly is. Kant is therefore the philosophic godfather of nihilism.

Unlike Hume, though, Kant was not quite a thoroughgoing skeptic. Instead, his goal was to downgrade what reason can know so that religion might be saved from reason and reality. The German philosopher’s highest goal was to build a non-rational bridge from man to God. In Kant’s famous words, “I have therefore found it necessary to deny knowledge, in order to make room for faith.” In order to do this, however, Kant had to subordinate, limit, and cordon off what reason can know. By limiting what reason can know to the world of phenomena simply, Kant built a “No Trespass” sign at the entrance to his bridge that made reason off limits to religion and religion off limits to reason. Indeed, what Kant ultimately achieved was to have built the original Bridge to Nowhere!

Having destroyed the pretensions of Enlightenment reason and science, Kant believed that “all objections to morality and religion will be for ever silenced, and this in Socratic fashion, namely, by the clearest proof of the ignorance of the objectors.” Kant’s philosophic coup d'état represented the philosophic death of the Enlightenment and its hopes of establishing the reality and the importance of “truth” in human affairs.

Thus, in one fell swoop, the four “truths” of the Declaration of Independence were reduced to mere opinions. Not surprisingly, the principles and institutions established by America’s revolutionary generation rested on a foundation of assumptions that would soon develop philosophic fissures. The founders got us most of the way, but the moral foundation they laid and the political structure they built needed fortification. In other words, built into the fabric of America’s original political system were the seeds of its own destruction, thereby making it an easy target decades later for the advocates of philosophic nihilism and political socialism.

Locke’s False Start

Before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let us pause for a moment and examine how the philosophic decline and fall of reason during the eighteenth-century impacted the moral foundations of the classical-liberal tradition. The pathbreaking accomplishments and the disappointing failures of the Enlightenment are seen most notably in the ideas of John Locke, the late seventeenth-century English philosopher. Locke is commonly and rightly identified as the philosophic father of the classical-liberal tradition. There were many other philosophers who helped to develop the principles of what would later become known as Enlightenment or classical liberalism, but Locke was undoubtedly the most influential. His best-known work, the Second Treatise of Government (1690), established the core political principles of a free and just society, but it was his much more philosophically abstract and difficult treatise in epistemology (the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of knowledge and how it is acquired), the Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), that attempted to establish the moral foundations of a free society via reason. As noted already, a primary goal of the Essay was to ascertain what it is possible for men to know and not know with regard to their conduct.

A demonstrative science of ethics requires two related things: a systematic moral code that can be rationally proven to be objectively true. Morality, Locke thought, was fundamentally an epistemological issue—that is, it stands or falls on the ability of philosophy to establish the efficacy of reason. Locke’s great ambition was to identify the moral laws of nature or what might be called a demonstrative science of ethics, one grounded in nature and human nature and discovered without the aid of revelation. Locke described his moral project in the Essay this way: “I am bold to think, that morality is capable of demonstration, as well as mathematicks: since the precise real essence of the things moral words stand for may be perfectly known; and so the congruity and incongruity of the things themselves be certainly discovered.” In other words, Locke was looking to establish a secular science of ethics that was certain, objective, and absolute and that did not require the assistance of revelation. Locke teases readers of the Essay in no fewer than six places with the prospect that he is seeking to develop “moral rules” that are “capable of demonstration” and “rules of action” that would be as “incontestable as those in mathematics.”

The search for a demonstrative science of ethics grounded in man’s nature represented a philosophic Holy Grail for the thinkers of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment. Locke teased his readers in the Essay that he was leading the search. One of Locke’s closest friends, William Molyneux from Ireland, wrote to the philosopher in 1692 shortly after he had finished reading the Essay, and pleaded with Locke to finish the quest. Molyneux wrote:

One thing I must needs insist on to you, which is, that you would think of obliging the world with “A Treatise of Morals,” drawn up according to the hints you frequently give in your essay, of being demonstrable according to the mathematical method. This is most certainly true. But then the task must be undertaken, only by so clear and distinct a thinker as you are. . . . And there is nothing I should more ardently wish for than to see it.

Locke responded to Molyneux’s request with caution. In fact, he hedged his bet:

Though by the view I had of moral ideas, whilst I was considering the subject, I thought I saw that morality might be demonstratively made out; yet whether I am able so to make it out, is another question. Everyone could not have demonstrated what Mr. Newton’s book hath shown to be demonstrable; but to show my readiness to obey your commands, I shall not decline the first leisure I can get to employ some thoughts that way.

Notice Locke’s qualifications and hesitations. Over the course of the next few years, Molyneux repeatedly asked Locke about his progress in developing a secular science of ethics. In fact, he pleaded with Locke to get to work on his projected treatise on ethics. The Irishman told his friend that it would be a “great good to the world” and that “no age ever required it more than ours.” Locke’s responses were at first evasive, then he virtually stopped replying to Molyneux’s repeated entreaties, and finally, he diplomatically suggested to his pestering friend that he stop asking.

Tragically, Locke’s search for and attempt to build a demonstrative science of ethics failed. The Englishman could never validate as certain the knowledge gained by reason, and he was unable to establish a demonstrative science of ethics—a science of ethics that could provide the necessary moral foundation for his revolutionary political system. Locke’s failure to establish a secular moral code led him to his default position, which was to equate the moral laws of nature with New Testament morality. Consider what Locke says in The Reasonableness of Christianity (1695):

It is too hard a task for unassisted reason to establish morality in all its parts, upon its true foundation, with a clear and convincing light. And it is at least a surer and shorter way, to the apprehensions of the vulgar, and mass of mankind, that one manifestly sent from God, and coming with visible authority from him, should, as a king and law-maker, tell them their duties; and require their obedience; than leave it to the long and sometimes intricate deductions of reason, to be made out to them. Such trains of reasoning the greatest part of mankind have neither leisure to weigh; nor, for want of education and use, skill to judge of. . . .

Whatever . . . the cause, it is plain, in fact, that human reason unassisted failed men in its great and proper business of morality. It never from unquestionable principles, by clear deductions, made out an entire body of the “law of nature.”

And he that shall collect all the moral rules of the philosophers, and compare them with those contained in the New Testament, will find them to come short of the morality delivered by our Saviour, and taught by his apostles; a college made up, for the most part, of ignorant, but inspired fishermen.

One might very well trace the beginning of the philosophic decline and fall of the Enlightenment to 1695 (just five years after reaching it apogee), when Locke ended his quest to discover a demonstrative science of morality and instead returned to what he called the “College of Ignorant but Inspired Fishermen” for moral sustenance.

The Beginning of the End

The response by various eighteenth-century moral philosophers to Locke’s failure to develop and establish a demonstrative science of ethics was not to pick up where the Englishman left off, but rather to abandon and then reject the project all together. British and French Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment thinkers—men such as the Lord Shaftesbury (1671-1713), Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), Lord Kames (1696-1782), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), and even Adam Smith (1723-1790)—restored the old doctrine of innate ideas in one form or another and applied it to morality.

Consider, for instance, the views of Locke’s former homeschool student, Anthony Ashley Cooper (Third Earl of Shaftesbury), who privately accused his former teacher of being a secret follower of Thomas Hobbes and of striking “at all the fundamentals” of morality. Shaftesbury charged his old tutor with throwing “all order and virtue out of the world and made the very idea of these . . . unnatural and without foundation in our minds.” (In other words, he denounced Locke’s moral philosophy as leading to hedonism and libertinism.) According to Shaftesbury, Locke’s moral theory threatened to level moral thought and action because it could not ground virtue on a firm foundation:

. . . Virtue, according to Mr. Locke, has no other measure, law, or rule, than fashion or custom; morality, justice, equity, depend only on law and will. . . . And thus neither right nor wrong, virtue nor vice, are anything in themselves; nor is there any trace or idea of them naturally imprinted on human minds. Experience and our catechism teach us all!

Shaftesbury was disturbed by both the content and the source of Locke’s moral theory: he rejected Locke’s individualistic, self-regarding ethical teaching and the possibility that the source of morality could be discovered in some place other than as an innate command from God, both which he saw as a threat to “order and virtue.” Shaftesbury’s point was this: Locke had enfeebled moral virtue by undercutting its natural foundation (i.e., that it is “imprinted on human minds”) and tying it to self-interest and opinion (which means, from Shaftesbury’s perspective, subjectivism and relativism).

By contrast, morality for Shaftesbury (and for virtually the entire history of moral philosophy) is “doing good for good’s sake, without any farther regards, nothing being truly pleasing or satisfactory but what is thus acted disinterestedly, generously, and freely. . . .” Moral action is only moral for Shaftesbury if the actor receives no benefit from it. Shaftesbury’s moral code required of men that they throw “aside selfishness, mercenariness, and such servile thoughts as unfit us for this world.” Shaftesbury was attempting to save religion and traditional feudal morality from the revolutionary implications of Locke’s teaching. The road to Kant was paved by Shaftesbury.

Locke’s failure to build a demonstrative science of ethics that would ground and validate the philosophy of freedom and individual self-interest created an epistemological-moral vacuum that was ultimately filled by its enemies. In the century after Locke’s death, no one came to his philosophic defense. No one attempted to finish what the Englishman started. In fact, most eighteenth-century moral philosophers, including many that we consider to be in the classical-liberal tradition, moved away from the implications of Locke’s radically individualist philosophy. It was now a short hop, skip, and a jump to Kant’s totalizing and all-consuming morality of mindless self-sacrifice.

The “All Destroyer” Moves in for the Kill

Kant’s moral theory represents the final denouement of the Enlightenment and its attempt to build a moral foundation that could ground the political structure built by America’s founding fathers. In the history of moral thought, Kant was the ultimate philosopher of self-sacrifice. He took the moral philosophy of selfless duty that came to him from the Platonic and Christian traditions and raised it to its highest pitch and logical conclusion. With Kant’s moral philosophy, the aspirations of the Enlightenment died. In the paragraphs that remain, I shall draw on four of Kant’s most illuminating works on moral philosophy, namely, Lectures on Ethics (1775-1780), Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), and Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone (1793), and On Education (1803).

If the freedom and right to the “pursuit of happiness” represents the highest moral ideal of the Enlightenment and the founders’ liberalism, then Kant was its greatest enemy. Happiness and its pursuit (via freedom) have very little moral standing for Kant—in fact, as he wrote in the Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, he “considers the principle of one’s own happiness [as] the most objectionable of all”—precisely because men naturally pursue it (grounded as it is in man’s natural inclinations, feelings, impulses, and desires), thereby providing them with “incentives” to act virtuously. He recognizes and hates the fact that happiness is actually experienced by individuals and is therefore a selfish pursuit, which means that it can have no moral standing. Kant is thus contemptuous of those “boasting eulogies” by those philosophers who speak of the “advantages of happiness and contentment” as the end of life. For the Prussian philosopher, morality should not be viewed as a means-to-an-end, e.g., happiness. Virtue must be seen simply as an end-in-itself with no view to bettering one’s life or achieving happiness.

Kant’s moral philosophy begins with a view of human nature that might have made John Calvin wince. The Prussian philosopher believed that mankind in general have, including even the best of them, what he described in his Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone as a “propensity to evil.” It is not that men are flawed, weak, or fallible for Kant; it’s that evil is “woven into human nature,” that man is “evil by nature,” that there is a “radical innate evil in human nature.”

And what is the source and nature of this evil that lurks in the hearts and minds of men? Kant’s answer is clear and unambiguous: man is propelled by “self-love,” which “is the very source of evil.” But what makes man’s evil so genuinely reprehensible for the Prussian is that all men choose to be evil, i.e., to be self-interested. Kant recognizes that men are partly compelled by inclination, but he also recognizes that they also have free will and they choose, regrettably, to pursue their self-regarding values and goods.

Kant’s positive moral philosophy can be found most especially in his Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals. True morality for Kant is that which transcends and overcomes man’s “wants and inclinations,” that is, his selfishness. For Kant, man’s will is free to escape from reality (i.e., experience, necessity, and inclination) to a higher, non-worldly realm (i.e., the noumenal realm), which is where he will find the possibility of true morality. From history, experience, and even from human nature, Kant says, we can learn nothing about the proper principles of morality. The only morality that counts for Kant is the kind that requires the “submission of my will to a law without the intervention of other influences on my mind.” In other words, Kantian morality means the freedom to choose obedience to a commandment that is untouched by self-interested motives. The actions of the virtuous man must never be motivated by personal pleasure, gain, or profit.

In Kant’s mental universe, the highest form of morality is born of, and rests within, man’s mind in the form of “pure reason.” What Kant calls the “metaphysics of morals” is disconnected from reality and man’s phenomenal nature. Man can access the noumenal or “intelligible world” by transferring or transporting “himself into an order of things altogether different from that of his desires” and inclinations. There, in a world divorced entirely from all self-regarding motives and automatic inclinations, men will discover pure moral commandments devoid of personal interest. Such commandments require unconditional obedience, which is man’s highest duty.

The ethical gold standard for Kant is a series of absolute, unconditional commandments that he calls “categorical imperatives,” which are rules that are simply good-in-themselves, regardless of their result for oneself. These categorical imperatives must be disconnected entirely from any motives or incentives that would lead to any possible good or selfish results for the actor. Kant’s two prime directives command men to:

1. “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

2. “Act so that you treat humanity, whether your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never as a means only.”

What exactly do these rather vague commandments mean in practice? How, for instance, can the treatment of humanity as an end become a universal law?

Kant put flesh on the bones of his categorical imperatives in his Lectures on Ethics, particularly in the lectures on “Duties to Others,” “Duties Dictated by Justice,” “Poverty and Charity,” “Duties Arising from Differences of Age,” and “The Ultimate Destiny of the Human Race.” In the essay on “Duties to Other Men,” Kant is most concerned to define the duties we owe to other men, which he describes as duties of “indebtedness or justice.” According to our Prussian philosopher, all men owe a compulsory debt (i.e., a duty) to all others who have less material wealth. This debt stems from the fact that all men have an “equal right,” that is, a natural claim to an equal share of nature’s bounty. The equal right of the poor, for instance, to the “good things of life” must not be denied; instead, “it must be satisfied.” Likewise, the man who has more wealth than he naturally deserves is obliged to share his wealth and to “restrict [his] consumption.” Kant treats those who have more than others not as creditors (as one might expect) who loan or even give money to those who have less but as “debtors,” who have an unchosen moral duty to sacrifice the fruits of their labor for the sake of others. But it’s not good enough for Kant to say that men owe others in their particular community a debt; he goes much further and claims that we owe a debt to “mankind,” who have a “rights” claim against our lives, our liberties, our property, and our pursuit of happiness.

As an example of one’s duties to others, Kant considers the example of charity. He dismisses charitable acts pursued out of benevolence, kindness, or even love because benevolence, kindness, and love partake of inclination or instinct (e.g., sympathy), whereas charity practiced as an entirely non-self-interested, non-gratifying duty has moral standing in Kant’s view. In fact, he goes further. Kant suggests that distinctions between rich and poor are entirely arbitrary and grow out systemic injustices. “Charity” given out of selfless duty is a form of “restitution” or restorative justice to men whose dignity requires that they be made whole by those who have benefitted from some kind of undefined systemic exploitation. In Kant’s words,

[f]or if none of us drew to himself a greater share of the world’s wealth than his neighbor, there would be no rich and poor. Even charity therefore is an act of duty imposed upon us by the rights of others and the debt we owe to them.

Thus, we have in Kant the idea that the world naturally is or should be owned by man in common, that inequality can only be explained by exploitation or theft, that men have original rights to the wealth of others, and that justice demands of men that they accept their moral duty to share their unjustly acquired wealth with those to whom they owe a moral debt. The just man for Kant will be benevolent, not as an inclination but as a trained, compulsory duty, such that it will become “the sole rule of his conduct.” Kant is the first moral egalitarian in history. The road to Marx and Rawls was paved by Kant.

Kant’s categorical imperatives are unconditional commandments that must be obeyed selflessly and unquestioningly. To obey the categorical imperatives as an unthinking automaton is man’s highest virtue. (To be clear: all of Kant’s talk about “pure reason,” “freedom,” and “autonomy” is just so much Orwellian doublespeak that dishonestly highjacks and corrupts the language of Enlightenment liberalism.) Kant’s moral man does not, or at least should not, act from his self-regarding rights in order to achieve his values, goods, and happiness (which would be to act from selfishness), but from his duty to be obedient to the commands of the categorical imperative, which is a floating abstraction with no connection to reality. In other words, Kant’s morality preaches self-renunciation as one’s highest duty and duty is an end-in-itself. Any action that contains the smallest admixture of self-interest is tainted for Kant. For instance, if you take pleasure in helping others, your actions are at best morally neutral. Kant’s ethics can be summed quite simply: it’s sacrifice for the sake of sacrifice, duty for the sake of duty, and obedience for the sake of obedience.

And how, for Kant, shall men actually become moral? How will they reach “the destined final end, the highest moral perfection to which the human race can attain”?

Kant’s answer is, as it has been for all moral totalitarians throughout history, to indoctrinate children, who must be “disciplined” to obey via “compulsion.” Not surprisingly, Kant was one of history’s first proponents of compulsory government schooling. In his small treatise On Education, the German philosopher announced that children should be sent to government schools in order “that they may become used to . . . doing exactly as they are told.” Such schools must be managed by the “most enlightened subjects,” who will use various forms of compulsion and “discipline” to make children “learn submission and positive obedience.” Children will be forced to memorize a “catechism of right conduct,” which is the first step to learning and being obedient to the categorical imperatives. When children are educated to obey their masters and maxims, they will have been prepared to follow their political leaders as adults. Children must learn “absolute obedience to [their] master’s commands,” which will prepare them “for the fulfillment of laws that [they] will have to obey later,” as citizens, “even though [they] may not like them.” Not surprisingly, disobedient children and disobedient citizens must be punished.

As we’ve now seen, Kant’s epistemology is the deepest philosophic source of the coming nihilism announced by Friedrich Nietzsche at the end of the nineteenth century, and his moral philosophy is the source of the various socialisms (national and international) that disgraced the twentieth century. By disassociating moral virtue from the naturally occurring and morally necessary human pursuit of self-interested values and goals, Kant was the destroyer of human happiness qua happiness. In the words of his contemporary, Moses Mendelssohn, Kant was “the all-destroyer.”

'Kant’s answer is, as it has been for all moral totalitarians throughout history, to indoctrinate children, who must be “disciplined” to obey via “compulsion.” ' This paragraph was the payoff, the cash value, of this excellent essay. I was fairly familiar with Kant, but never got the connection to indoctrinating children. In this way at least, Kant is the son of Plato, who must be looking down and laughing at us all.

So is it any wonder that there are two different world views, and the complaint is that there is no unity, and one screams "extremist", and the other scratches his head in wonderment?

This is excellent, and if you made it into a pamphlet, I would definitely buy it and recommend it.