College "Move-In Day"--Army Style

Commentators on American society often speak of the “two Americas.” America is divided, they say, between, liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, blue staters and red staters, rich and poor, black and white, etc. But there is another division in the United States that is rarely, if ever, talked about—the division between those teenagers who go to college and those who join America’s armed forces.

I’d like to share two very different stories with you about a drama played out every year in America during the months of August and September. The drama is uniquely American. These two stories are connected to our deepest hopes and aspirations, and they partially explain the “two Americas.”

Move-In Day #1

In August and September of every year, a million or two seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds leave home, usually with their parents in tow for the day, and they move into their college dormitory. It’s quite an event. After three months of summer quiet, America’s colleges and universities suddenly explode with activity and excitement.

I’ve been a college professor for 28 years, and I have three adult children all of whom graduated from college in the last few years. I’ve therefore witnessed or participated in many college “move-in” days for entering freshmen. It’s a fascinating sociological phenomenon to observe.

New college students and their parents have been preparing for this day for months, if not years. Move-in day is the culmination of their hopes and dreams. Mom and dad started the kids’ college fund on the day each of them was born. The kids have been dreaming for the last year or so about leaving home and starting off the first great journey of their lives.

Socio-economically, most college students, or at least the ones I see, usually come from middle- and upper-class families. Their parents are typically lawyers, doctors, bankers, business executives, or work in the high-tech industry. Mom and dad are usually tanned, having just spent the last weeks of summer at the beach; they’re well-manicured, and they roll up to their son or daughters dormitory driving big Suburban SUVs, BMWs, or Mercedes and towing U-Hauls. Many of these new college students come with cars their parents bought for them when they graduated from high school. I’m not sure if I’m bemused or irritated by the fact that many of my freshmen students drive significantly better cars than I do!

These college-bound students were most often the best and brightest at their high school. As high school seniors, these over-achievers took a senior cruise for Spring Break, and they had big parties when they graduated. Maybe they interned over the summer with a local congressman.

College move–in day is a happy occasion, full of smiles and a few tears of joy. Mom and dad are bursting with pride. Move-in usually takes three or four hours. The family U-Haul has arrived with big screen TVs, refrigerators, and futons from IKEA. The kids meet their room- and floor-mates, whilst mom and dad meet the other parents. Dad sets up the futon, and mom decorates the room with posters and family photographs.

After everyone is settled, mom and dad take their son or daughter out for the last supper. Wanting to relive their own college experience, the parents insist that they all go out to the local pizza parlor. Supper is fun, with lots of laughter and reminiscences. Everyone is giddy with excitement.

It’s time to say goodbye. Mom and dad don’t go back to their son’s or daughter’s dorm room. That would be cringy and embarrassing. Instead, the three of them walk to mom and dad’s BMW. They hug. Mom is laughing between the tears. Dad is grinning ear to ear. They say goodbye and the parents drive off to be empty-nesters. Our new college freshman goes back to the dorm excited to begin the four best years of his or her life.

Move-In Day #2

Two years ago, I experienced a very different kind of move-in day that is unseen by most Americans. It’s the day when 100,000 or so young men and women around the country are inducted into America’s military services and go off to Basic Training or Boot Camp. It’s their version of college move-in day.

My second son, let’s call him Junior Redneck, had enlisted in the United States Army just before graduating from college. During his senior year, he came to me to announce that he wanted to delay going to graduate school because he was joining the Army. I was shocked, to say the least. He’d given me no prior indication that he’d been thinking about doing this. His reasons for enlisting were twofold: first, he said that he wanted to serve his country, which I thought was honorable, and, second, he thought the Army would be a great place to study human nature given that he hoped to do a Ph.D. in moral philosophy, which I thought was dubious. I told him that there might be better places or experiences in which to study the human condition without, ya know, getting shot at, but his mind was made up.

The summer before he left for Basic Training was filled with studying for the G.R.E and putting his affairs in order. Just like the summer before he left for college, Junior Redneck and I spent a lot of time talking about what he might expect from this new experience, how he could make the most of it, and what his exit strategy might be for leaving the Army after four years. With every passing day that summer, there was a sense of increasing anticipation.

And then the day came to drive Junior to Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, for his induction ceremony and the goodbyes. My wife and I drove down with Junior Redneck and his Redneck fiancé. When we arrived at the base, I immediately began to notice the differences between Army and college move-in day. The Fort Jackson parking lot for parents was not full of big SUVs, BMWs, and U-Haul trucks. Instead, the lot was full of pick-up trucks and old jalopies of one description or another. Some of the inductees no doubt arrived via the local bus system.

We then proceeded to go inside the assigned building and all of the inductees were sent immediately to separate rooms for processing. The families of these soon-to-be soldiers (i.e., parents, grandparents, siblings, girlfriends, boyfriends, fiancés, and a few spouses) were all herded into a small cafeteria where we sat at longhouse tables and waited impatiently for a good two hours.

These were not the same families I had seen on college move-in days. The social profile of these families was entirely different. The parents all seemed to come from various trades and service jobs. They mostly worked with their hands. I saw farmers wearing overalls, mechanics with thick hands and greasy fingers, and bonnet-wearing Chick Fil-A servers. The faces of the parents looked worn and prematurely aged. Many of the parents were taking off a few hours from their wage-labor jobs to see their sons and daughters inducted into the U.S. Army and leave for Boot Camp.

The air in the room was thick with a sense of nervous foreboding. Everyone seemed to speak in whispered tones, and they all bore reluctant smiles. It was not a happy room. Eventually, the inductees (about 125 of them) were brought into the cafeteria to talk to their loved ones. It was only then that I saw beaming smiles and a momentary relief in the parents’ eyes. The entire scene reminded me of a prison on visitation day.

And then there were the expectant soldiers, most of whom were young men. I was really quite surprised by what I saw. I was expecting to see clean cut, strapping young men with athletic physiques. There were almost none fitting that description. Most of them were physically unimpressive, and many of them struck me as small and scrawny. The facial expressions of these young men and women ranged from boredom to nervous trepidation. Furthermore, these young men and women were almost certainly not the best and brightest in high school. This was the group of kids who graduated in the bottom 25% of their class, if they graduated at all. Some of them no doubt had criminal records, or they were encouraged to join the Army to avoid a criminal record.

In words that I take no pleasure in writing or saying, what I mostly saw that day was a motley crew of seeming “dead enders” who had joined the Army because they had no option other than prison or rehab or nowheresville. This was their last chance to make something of themselves. I was instantly reminded of Lee Marvin’s great 1967 movie, The Dirty Dozen. (The Redneck Intellectual’s Millennial and Gen Z readers should check it out.) I was slightly appalled by what I saw, and I felt ashamed for thinking it.

Only a handful of the enlistees looked as though they might have been to college. At 22, Junior Redneck was one of the older inductees. Many of the young men and women with him didn't look much older than 17 or 18. Most of them could not have gone to college. They were all leaving home for the first time. For many of them, boot camp would be their first trip out of state if not the county. This group had never taken vacations to Europe with mom and dad or Spring Break cruises like the kids who went to college.

What struck me more than anything in that cafeteria was the number of young men who had no family members or friends there to say “goodbye” to them. They stood alone along the wall as the other inductees spoke to their families. Those who stood alone tried to look as if they didn’t care, but their look of fidgety nonchalance revealed a degree of embarrassment and disappointment and maybe even a bit of resentment. I now regret not having gone over to each one of them to shake their hands and to thank them for serving our country.

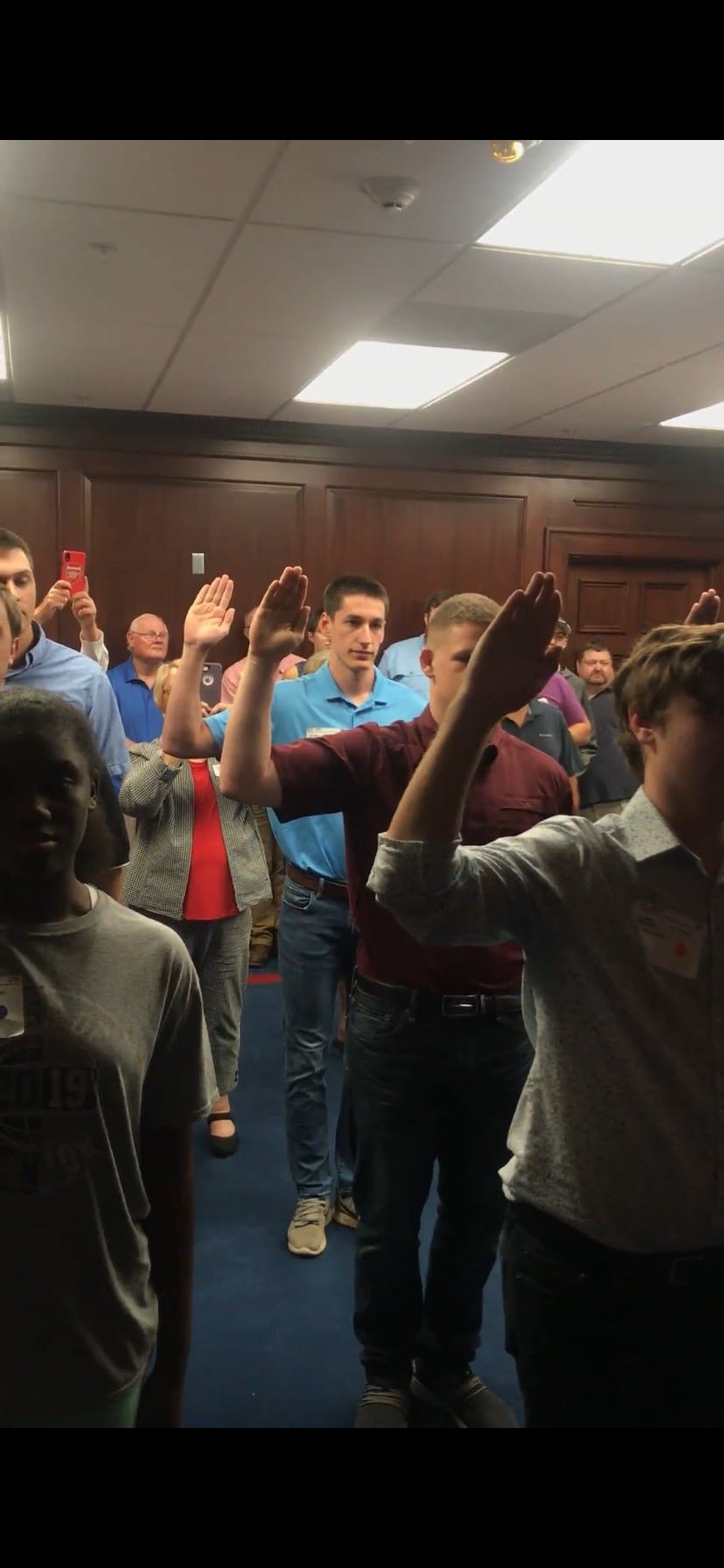

Finally, the time arrived for the induction ceremony. All of the inductees and all of their guests were herded into a tiny room where we all stood shoulder to shoulder. The inductees stood together at the front of the room to take their oath. The commander in charge of the ceremony began by saying, “Repeat after me. . . . I, state your full name _______.” To which half of the inductees repeated, “I, state your full name.” The induction ceremony took no more than a few minutes. The commander then turned to the audience and announced to the families that they had five minutes to say “goodbye.”

There was an audible gasp in the room. The inductees pushed their way through the crowd, almost always to their mothers first. In a heartbeat, the oxygen in the room was sucked out and replaced with the sound of sobbing mothers and girlfriends. Some of the young men started to cry as well as they hugged their mothers and girlfriends. In the mothers’ eyes one could see pure love and pure fear. Dad, with his tight-lipped smile, was always the last to be hugged. Now the crying stopped, although moist eyes there were. In the fathers’ eyes, one was only permitted to see immense pride.

And then, in a gut-wrenching scene that I will never forget for the rest of my life, I saw a young man turn from his sobbing mother to his waiting father. The father, who was clearly a veteran, sat in a wheelchair. He couldn’t get up to hug his son because he had no legs. The young man (with tears streaming down his face) bent over his father (with tears streaming down his face) and hugged him. The scene—simultaneously the most beautiful and the most painful thing I’ve ever seen—was simply more than I could bare to see. I was gutted and turned away barely able to control my emotions.

This was not the same as college move-in day. Unlike those parents who drop off and say goodbye to their teenage children at college, the parents of these enlistees were no doubt overwhelmed by one, all-consuming thought: goodbye might be forever.

In just a few minutes, we all said our good-byes and then the inductees were hustled out of the room. Later that day, Junior was put on a plane and flown to Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri to begin Basic Training. He was gone. (Junior subsequently reported that once he and his fellow soldiers arrived at their barracks, fist fights broke out within days. Once again, not your typical freshman orientation-week experience.)

Mrs. Redneck and I got in the car and went out for lunch. Nary a word passed between us. We were both still overwhelmed and numbed by the Army’s move-in day. After lunch, we got back in the car and drove home not saying a word to each other. That car ride was the longest two hours of my life. My wife and I couldn’t look at each for fear of saying out loud that which must not be said.

I thought long and hard about what I had experienced that day. But as I drove along the empty highway I was overcome by a sense of swelling pride, not just for my son, but for all of the enlistees and families that I saw that day. This was my America. I was also proud of the United States Army, because I knew that the ragtag group of men and women who had been inducted into the Army that day would come out the other end as different men and women. They would no longer be losers and dead-enders. I knew the Army would whip them into shape and make them into a real fighting force, and that’s a very good thing.

Whereas America’s colleges and universities take America’s best and brightest and turn them into whining and sniveling wokesters, the armed forces take America’s teenage dead-enders and produce the best amongst us. RESPECT!

I was humbled and honored that day to attend the induction ceremony for my son and 125 other young men and women who joined the United States Army with him. It was the best “move-in day” ever. I am not a religious man, but I would like to say to all the young men and women who took an oath that day to uphold the United States Constitution and to defend America, "Thank you, and God Bless You!"

Hooah!

(Please consider being a paid subscriber.)

“In words that I take no pleasure in writing or saying, what I mostly saw that day was a motley crew of seeming “dead enders” who had joined the Army because they had no option other than prison or rehab or nowheresville.”

It stands as irksome that in the second America you describe, many of these young people either had nowhere else to go, or nothing else to do, and that therefore they may as well do the one thing they can do: join the military, in hopes to increase their prospects in life. Their direct purpose isn’t to fight for one’s country out of patriotic conviction, heroic ambition, or love of the good. Instead, the purpose is for the sake of all the materials benefits one can get - like any other job. What’s troublesome is not the desire to want to improve one’s lot in life, nor wanting to do so in the context of one’s own material benefit. What is troubling is how these young people could seemingly care less about the military; the growth and personal glory it can bring to an individual. It is treated like any other ‘dirty job,’ or any other paycheck/benefits program - essentially welfarism, one signed up for begrudgingly, with one’s life. Moreover, I often hear from young people in the military that they don’t even think the military is worth it, but at the same time, a mentality of, ‘What else is there?’ ensnares upon their spirits, one you captured poignantly.

You established that the military is a place thousands of young Americans - many poor and working class - go into not for any direct care or valuing of the military itself, but for non-military based reasons of material benefit, an umbrella of what government welfarism can offer (like full college tuition for example). And yet, *hundreds* of thousands of young Americans in the first America you describe who go to college have the same mentality as well, just in a different concrete form.

I am very confident in saying that almost all young Americans who go to college go because of the conformity effect, (“Well, this is what everyone else my age does,” “What other option is there/What else is there?”) or for the sake of a well paying job. Like before, the issue isn’t to want to progress in life for the latter motivation. The issue is that these young people are in college not for colleges’ sake, but for what a piece of paper begotten after four years can afford them. Like the young military enlistees, young college enlistees are in college for indirect purposes; both sets of young people in their respective next four years not for what they can get *from* their institutions, but what they can get *out* of them. They could care less about what the *military* or *college* can bring to them - the institutional experience, the wisdom, the knowledge, the growth. Instead, what they want is either full paid tuition for college, military benefits; or, a piece of paper (the “signal” to employers) and wasteful fraternizing, like one big long four-year vacation, respectively. The only difference, again, is how this mentality of, “What else is there?” concretely takes shape, (and the fact I think that young people in the military are more honest and transparent about their mentality.)

It goes without saying, that our young people in this country are being let down by the adults in their society, in proportions that future generations will look down upon and see as one of the worst unspoken tragedies in man’s history: wasted human potential, ability, and lives on mass scales.

Take heart about your son. I was in his position almost 30 years ago. I had just graduated from a well known east coast school, with a degree in accounting, headed towards law school. I had what I call a midlife crisis at 21. I enlisted in the Infantry with a Ranger contract. After six years service, I got out and decided to go to medical school. Accepted to medical school at 30 years old, I have been practicing medicine for almost 20 years.

To this day I am more proud of my time in service than any other accomplishment. I learned how to appreciate the essentials; e.g. a warm, dry place to lay down at night, any food, and the ability to laugh during miserable conditions.

You will be amazed at the things your son will learn in the Army, lessons that are not taught in undergrad. The United States Army has over 240 years teaching young men and women how to be self reliant, self disciplined, goal oriented individuals. I believe you and your wife will be pleasantly surprised at the ways he will change and grow.

God Bless, and please tell your son, “Thank you for your service,” from someone that is now relying on the security he and his comrades provide.