Alexis de Tocqueville and Self-Interest Rightly Understood

Part 8 in a series . . .

***The audio version of this essay can be found at the bottom.

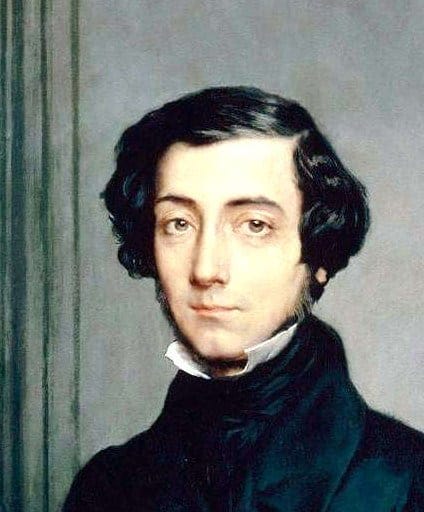

In 1831, the French aristocrat, political philosopher, moral psychologist, and social commentator, Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859), arrived in the United States accompanied by his friend, Gustave de Beaumont (1802-1866). The two young men spent nine months traveling around America, north and south, east and west. The ostensible purpose of their trip was, on commission from King Louis-Phillipe, to examine America’s prison system. Upon their return to France, the duo published a two-volume treatise, On the Prison System in the United States and its Application in France (1833).

During their American tour, Tocqueville and Beaumont studied more—much more—than America’s prison system. The pair conducted hundreds of interviews, attended scores of political meetings, studied countless legal and political documents, and recorded their observations on American society, politics, and culture. As a result of his American studies, Beaumont also published a two-volume novel and social commentary on slavery in America titled, Marie, or Slavery in the United States (1835).

Tocqueville’s ambition, certainly his philosophic ambition, was greater than his companion’s. The initial purpose of Tocqueville’s trip was to observe, record, and ultimately to reflect upon the nature and meaning of America’s democratic institutions, but in the end, he went deeper and came to understand the manners and mores of the American people and ultimately the nature of the American character. The Frenchmen saw between the seams of American life. He saw things about the Americans they did not know about themselves. The result was not only the greatest book ever written on America, but also one of the greatest works of political philosophy ever written.

Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, published in two volumes (1835 and 1840), is a literary masterpiece of philosophic observation and reflection on the causes and consequences of a social revolution that he believed was changing the world forever. The Frenchman’s book was a profound meditation on the soul of democratic man and the “irresistible” democratic virus that was sweeping the Western world. The Frenchman saw in America the advent of a new kind of man, forged on the crucible of equality, freedom, and, most shockingly, self-interest. This new human-type observed by Tocqueville was unknown to all civilizations hitherto. His description of the American merchant entrepreneur or the frontier pioneer had no parallel in Socrates’s Athens, Cicero’s Rome, Machiavelli’s Florence, Voltaire’s Paris, or Samuel Johnson’s London.

Tocqueville came to America to see the future. The 700-year-old ancien regime of the Old World was dying and Tocqueville hoped to guide France as it transitioned to a new world defined by equality and freedom. All of France’s social and political institutions as well as its manners and mores were undergoing profound change. During his lifetime, Tocqueville witnessed the aftermath of the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the shaky restoration of the monarchy. In 1830, just before he set sail for America, the July Revolution had overthrown one king (Charles X) and installed another (Louis-Philippe).

The Old World of aristocratic manners and mores, social conventions, and political institutions was imploding, and Tocqueville viewed American democracy as a beacon of hope for France’s future in the same way that the seventeenth-century Puritan, John Winthrop, saw America as a “City Upon a Hill” for England. Democracy for Tocqueville was more than a political system or form of government; it was a way of life expressed in certain social manners and mores.

What did Tocqueville see in the United States? What was the new society and way of life emerging from the principles and institutions created by America’s founding fathers?

As we saw in “The Founding Fathers’ Moral Revolution,” America’s revolutionary founders created a new kind of political society—what we might call a natural-rights republic—grounded in moral principles such as freedom, rights, and self-interest. Given the safe space and elevated role that America’s founding fathers created for self-interest in human relations, how did this revolutionary moral vision play out in American culture throughout the nineteenth century? What kind of society flowed from the moral, cultural, and institutional liberation of individual self-interest?

In what follows, I shall focus on Tocqueville’s view of what he called “the doctrine of self-interest well understood,” or, as rendered by other translations (which I prefer, at least rhetorically), self-interest “rightly” or “properly” understood. To fully understand this concept in Tocqueville’s thought, it must be put in the larger context of Democracy in America as a whole and seen in the light of his use of related concepts such as “equality of conditions,” “democracy,” “individualism,” “selfishness,” and “soft despotism.” Tocqueville was an acute observer and prognosticator of a revolutionary moral doctrine that had been given birth in the United States.

Tocqueville’s Hypothetical

In a fascinating letter to Ernest de Chabrol written from New York on June 9, 1831 (a month after he and Beaumont arrived in the United States and long before he sat down to write Democracy in America), Tocqueville asked his friend to imagine a hypothetical, multicultural society in which people from “all the nations of the world” were all mixed together de novo (an obvious reference to the United States). Such a nation would be rootless, he noted, and “without memories, without prejudices, without routines, without common ideas, without a national character.” This new nation would be a cultural tabula rasa, and so the obvious question that Tocqueville planned to address was: what would hold it all together? What would serve “as the link among such diverse elements?” What would make all of them, Tocqueville asked, “into one people?”

The Frenchman’s answer was simple and, in many ways, shocking, but it also represented a profound rethinking of what society is and what holds it together. If this imaginary new society had no meaningful past (at least not in the European sense) and no common traditions, then all these separate cultures and discrete individuals would quickly have to discover that one characteristic they all share, which is, it turns out, self-interest. “Interest,” Tocqueville suggested, is the social glue—as with Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”—that collates all the separate parts into a single whole. “That,” Tocqueville announced, “is the secret,” the revolutionary insight that reveals a new way of thinking about moral, social, political, and economic organization. For Tocqueville, the United States of America is that place where “private interest” was united with the “general interest,” and, as a result, the society was “well ordered.” Ironically, it turns out that individuals all pursuing their self-interest is the secret adhesive that binds the parts into a harmonious whole. What Tocqueville saw in America cut against the grain of 2,500 years of moral philosophy and practice.

In the New World, private interest was turned, Tocqueville observed, toward innovation, production, wealth creation, and the pursuit of happiness. No human civilization through all history had seen anything like it. The Frenchman was mesmerized by what he saw in America:

Nothing is easier than becoming rich in America; naturally, the human spirit, which needs a dominant passion, in the end turns all its thoughts toward gain. As a result, at first sight this people seems to be a company of merchants joined together for trade, and as one digs deeper into the national character of the Americans, one sees that they have sought the value of everything in this world only in the answer to this single question: how much money will it bring in?

What Tocqueville is here describing represents a moral revolution in human thought and action. The selfish pursuit of wealth and therefore self-improvement was now recognized for the first time in history as a not only morally acceptable but as laudable.

What made all this possible?

In America, public power was shackled and shrunk, thereby liberating and expanding the private power of millions of ordinary people. In Europe, by contrast, public power was liberated and expanded, thereby shackling and shrinking the private power of ordinary men and women.

In Tocqueville’s America, the purpose and function of government was to serve the private interests of ordinary men and women by protecting them from ambitious men but otherwise leaving them alone. In the United States, Tocqueville told Chabrol, “there is no public power, and, to tell the truth, there is no need for it.” In America’s nineteenth-century, night-watchman government “political careers are more or less closed,” which means that “a thousand, ten thousand others are open to human activity.” As a result, the “whole world here” is “open to industry,” and there is “no man who cannot reasonably expect to attain the comforts of life: there is none who does not know that with love of work, his future is certain.” The idea that men and women could “love” their work—could love it not because it put food on the table and paid the bills but because they gained from work satisfaction in creativity, production, and trade—represented a moral revolution in human thought and action. History records no philosopher or society that promoted work as something other than painful, necessitous drudgery. The pursuit of individual self-interest in America was now seen as morally liberating, socially democratic, and even morally ennobling.

Why Tocqueville Came to America

For Alexis de Tocqueville, America was a philosophic laboratory in which a grand social experiment could be observed unfolding. The United States was unlike any other country in world history. The Frenchman viewed America as having unleashed a democratic revolution upon the world grounded in what he called the called the “equality of conditions” that was in the process of breaking up and destroying the ancien regime. The “same democracy,” he saw “reigning in American societies” was now “advancing rapidly toward power in Europe.” The question was whether France and the rest of Europe were ready for the arrival of American democracy. Not surprisingly, then, Tocqueville came to America with a certain degree of fear and trembling.

In his introduction to Democracy in America, Tocqueville told his readers that he came to the United States to both see where France and the rest of Europe was headed, and he also hoped that he might be able to promote those American virtues that could be adapted to conditions in France while avoiding the vices unique to the American model. Tocqueville described his purpose in coming to America in these terms:

I confess that in America I saw more than America; I sought there an image of democracy itself, of its penchants, its character, its prejudices, its passions; I wanted to become acquainted with it if only to know at least what we ought to hope or fear from it.

Unlike France which was experiencing the transition to democracy somewhat chaotically and sometimes violently, America seemed to have been born democratic and had managed to reconcile equality with liberty and stability. America, though not perfect, represented the best that could be expected from a free and democratic society.

Tocqueville’s initial purpose in coming to the New World was to study the political and social institutions unique to the United States, and, more importantly, the “habits of the heart” (i.e., moeurs) that allowed the American people to maintain freedom and social order. In short, Tocqueville hoped to observe and dissect the Americans’ various institutions and their manners and mores, so that he could return to France armed with a “new political science,” which is “needed,” he noted, “for a world altogether new.” The purpose of this reformed political science, he wrote, was to educate his fellow Frenchmen as they moved away from aristocracy and monarchy toward the seemingly inevitable rise of democracy as both a political system and a way of life. His goal was to guide the French nation as it deconstructed the ancien regime and drove toward constructing a new kind of society. Tocqueville’s purpose in writing Democracy in America was, if nothing else, ambitious:

To instruct democracy, if possible to reanimate its beliefs, to purify its mores, to regulate its movements, to substitute little by little the science of affairs for its inexperience, and knowledge of its true interests for its blind instincts; to adapt its government to time and place; to modify it according to circumstances and men: such is the first duty imposed on those who direct in our society today.

Tocqueville therefore wrote Democracy in America as a political guidebook for France’s ruling class. In essence, he was telling his compatriots that they could not navigate the future by reminiscing about the past. France was becoming a new kind of society whether they liked it or not, which meant that it required a new way of thinking about politics and society, manners and mores, and freedom and equality. Democracy in America is book about democracy in France and the rest of the Old World.

What Tocqueville Saw in America

Not surprisingly, the first thing that caught Tocqueville’s aristocratic attention when he arrived in America was the “equality of conditions” which he found throughout the new republic. The Frenchman described this state of affairs as the “generative fact from which each particular fact seemed to issue.”

In stark contrast to France and the rest of continental Europe, America had no peasantry, no proletariat, and no aristocracy. For a French aristocrat accustomed to living in world defined by multiple layers of social, economic, and political hierarchy, America’s flattened social landscape would have struck him with a high degree of fascination and a small degree of trepidation. There was nothing in Europe to compare with what Tocqueville saw in America. The Frenchman went so far as to suggest that he wrote Democracy in America “under the pressure of a sort of religious terror in the author’s soul,” which was “produced by the sight of this irresistible revolution that for so many centuries had marched over all obstacles, and that one sees still advancing today amid the ruins it has made.” America was no doubt a model of what might or could be, but the question was whether the American model could be adapted to European conditions, particularly the uniquely American doctrine of self-interest.

Tocqueville’s view of America can only be fully understood in the context of what he left behind in Europe. The aristocratic ancien regime of the old world was rooted in, and bound together by, involuntary, hierarchical, traditional, social bonds that united society from top to bottom as an unchanging, unified, social whole. “Aristocratic institutions,” he wrote, “have the effect of binding each man tightly to several of his fellow citizens” in a “long chain that went from the peasant up to the king.” Every man in aristocratic societies is “placed at a fixed post” that comes with defined duties to those above and below one’s assigned station in life. Men and women were part of, and bound to, a socially organic whole that defined their identities via their relationships with others. The cultural structure of the ancien regime therefore created a tightly knit social fabric that provided little space for individual freedom of thought and action.

America was the antithesis of the ancien regime. “The great advantage of the Americans,” Tocqueville observed, “is to have arrived at democracy without having to suffer democratic revolutions, and to be born equal instead of becoming so.” America was different from Europe in almost every possible way. From the moment of its first foundings in the seventeenth century, England’s American colonies were defined by a high degree of equality and freedom. The chain of social hierarchy that Tocqueville said held European society together was broken in America, and a new-model man was birthed for a New World. This unprecedented human type was unlike any other in world history: he was an autonomous, equal, self-governing, and self-reliant individual who was free to forge his own path in life unrestrained by the status and conditions of his birth.

Despite his deep admiration for the virtues of America’s new-model man, Tocqueville also worried about and warned against certain vices associated with this new man and his new way of life. The equality, freedom, independence, and autonomy of America’s democratic way of life threatened to turn men in on themselves and to live—speaking colloquially—in their own “private Idaho.” The name Tocqueville gave to this way of life or social philosophy was “individualism,” which he said, “disposes each citizen to isolate himself from the mass of those like him and to withdraw to one side with his family and his friends, so that after having thus created a little society for his own use, he willingly abandons society at large to itself.” The result is that individualism leads to men to become “strangers among themselves,” and it leads each man to confine himself “wholly in the solitude of his own heart.”

(When Tocqueville introduces the topic of individualism, he speaks of it generally and in the context of “democratic countries” or of “democratic peoples.” In fact, he does not specifically mention Americans as exemplars of individualism, which is curious and somewhat confusing given the fact that the concept individualism—particularly in the form of “rugged” individualism—is most often associated with Americans. Tocqueville thus seems to be using a definition or form of individualism that is more applicable to Europeans than to Americans. This seems confirmed by the fact that Tocqueville argues that the Americans have found the antidote to individualism.)

Even worse than its isolating and bifurcating effects, democratic individualism will inevitably transform itself and descend into pure “selfishness,” which, for Tocqueville is the greatest vice or sin. “Selfishness,” the Frenchman claimed, “is a passionate and exaggerated love of self that brings man to relate everything to himself alone and to prefer himself to everything.” Pure or grasping selfishness is, he continued, “born of a blind instinct” and is a “depraved sentiment.” In other words, Tocqueville views selfishness as it had been seen by all philosophers and theologians dating back several thousand years to Plato. It is man’s greatest moral vice.

Even worse, Tocqueville viewed the degeneration of individualism into selfishness as not just a moral or social blight, but also as potentially leading to a political crisis that culminates in a uniquely modern form of tyranny, namely, “soft” or “mild” despotism. The problem that Tocqueville worried about was that a nation of isolated, inward-looking, and self-absorbed individuals would turn away from public concerns and permit a new form of bureaucratic tyranny to quietly and slowly centralize political power until an invisible Deep State has enveloped them without their noticing the chains that now enslaved them. This new form of despotism, Tocqueville predicted, would not resemble the brutalizing tyrannies of the past. Instead, the new tyranny “would be more extensive and milder, and it would degrade men without tormenting them.” Rather than wielding the tools of coercive force employed by traditional despots (e.g., the Rack or the Wheel), the new rulers of democratic man would come in the form of a bureaucratic army of tsk-tsking “schoolmasters.”

Tocqueville’s portrait of the degradation of democratic man into a form of non-rugged individualism and petty selfishness carries great force:

I see an innumerable crowd of like and equal men who revolve on themselves without repose, procuring the small and vulgar pleasures with which they fill their souls. Each of them, withdrawn and apart, is like a stranger to the destiny of all the others: his children and his particular friends form the whole human species for him; as for dwelling with his fellow citizens, he is beside them, but he does not see them; he touches them and does not feel them; he exists in himself and for himself alone, and if family still remains for him, one can at least say that he no longer has a native country.

From this banal state of existence would arise, Tocqueville feared, “an immense tutelary power” that would seek to take “charge of assuring” men of “their enjoyments and watching over their fate.” This soft, enervating despotism would resemble a form of “paternal power” that does not prepare “men for manhood,” but instead seeks to keep them in a state of perpetual “childhood.” This new form of despotism would willingly work “for their happiness; but it wants to be the unique agent and sole arbiter of that; it provides for their security, foresees and secures their needs, facilitates their pleasures, conducts their principal affairs, directs their industry, regulates their estates, [and] divides their inheritances.” Ironically, democratic individualism, once birthed in freedom, now slowly turned over its freedom to think, choose, and act to the faceless and always-scolding bureaucratic Nanny State.

Thus far, Tocqueville’s corrupted democratic man appears as a precursor to Friedrich Nietzsche’s soft and dilettantish “Last Man,” who turns in on himself and enjoys his petty pleasures now provided cafeteria-style by the State. Tocqueville’s description of the new despotism is chilling to twenty-first century readers because it seems to have come true in the post-WWII world. The democratic Deep State slowly suffocates democratic man:

[I]t covers the surface with a network of small, complicated, painstaking, uniform rules through which the most original minds and the most vigorous souls cannot clear a way to surpass the crowd; it does not break wills, but it softens them, bends them, and directs them; it rarely forces one to act, but it constantly opposes itself to one’s acting; it does not destroy, it prevents things from being born; it does not tyrannize, it hinders, compromises, enervates, extinguishes, dazes, and finally reduces each nation to being nothing more than a herd of timid and industrious animals of which the government is the shepherd.

This new administrative despotism is, according to Tocqueville, the ultimate consequence of the selfishness born of lumpen individualism. A citizenry that has lost its taste for public affairs and cares only for their private, material well-being will gladly trade its freedom for security and comfort. Freedom is not taken by a despot but sold to the highest bidder.

Saving Individualism with Self-Interest Well Understood

Tocqueville’s challenge in Democracy in America was to save democratic individualism from itself, that is, from its tendency to degenerate into grasping selfishness and all the psychological, moral, social, and political pathologies that go with it. In America, he found the antidote to individualism and selfishness. The Americans had developed, he argued, a potent cure for the maladies of European-style individualism and selfishness: what he called “the doctrine of self-interest well understood.”

As we saw in The Founding Fathers’ Moral Revolution, the idea of self-interest—the bane of moral philosophers and theologians for 2,000 years—was given its first serious hearing in America during the last quarter of the eighteenth and the first quarter of the nineteenth century. During Tocqueville’s nine-month visit to the United States between May 1831 and February 1832, he witnessed firsthand how nineteenth-century Americans lived out the “doctrine of self-interest well understood.” This was how the Americans overcame individualism, selfishness, and despotism, and it was the secret to their preservation of their liberty.

For centuries before the American revolution, possibly even millennia, the official moral doctrine of mankind was some form of selflessness and self-sacrifice. Tocqueville notes that the great thinkers and actors of history, both classical and Christian, “liked to form for themselves a sublime idea of the duties of man; they were pleased to profess that it is glorious to forget oneself and that it is fitting to do good without self-interest like God himself.” Classical, feudal, and early modern philosophers and statesmen were intoxicated with the “beauties of virtue,” which they always defined in one way or another as some form of heroic sacrifice.

Interestingly, Tocqueville seems to suggest that this kind of classical virtue was more imagined and wished for than practiced. (We should recall here that there was no small element of self-love in classical virtue [see Book IX of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics], which was performed less for the wellbeing and happiness of all and more for one’s own personal glory and honor.) In the modern world, however, a new form of morality developed, according to Tocqueville, that might be described as a form of universal goodwill and sharing. In other words, Christianity democratized sacrifice, which asked of men that they sacrifice for the sake of others.

In the United States, Tocqueville observed, Americans rarely talk about the loveliness of virtue in the way that European aristocrats once did. Instead, they talk about the utility of virtue as the means to bettering their lives and the lives of those around them. After two millennia, America’s new-model man had rediscovered and been “led back toward himself by an irresistible force.” In other words, this new moral code developed by the Americans begins with the “self” and not the “other” as the standard of value. Thus, the Frenchmen observed the rise of a new moral phenomenon in America largely unknown to moralists hitherto: “the doctrine of self-interest well understood.” This new moral philosophy, Tocqueville observed, has been “universally accepted” by the American people rich and poor, and it is “at the foundation” of all their actions. Indeed, it is their guiding moral philosophy.

The Americans, Tocqueville continued, “are pleased to explain all the actions of their life with the aid of self-interest well understood.” In fact, most Americans “think that knowledge of one’s self-interest well understood is enough to lead man toward the just and the honest.” The doctrine of self-interest rightly understood meant that individuals should and must choose by themselves and for themselves. In a free society, the sanction for an individual’s right to choose his calling, the wage and hours for which he would work, the price he would charge, the buyers to whom he would sell, and the way he would accumulate and spend his wealth was grounded in the natural-rights philosophy that guided and defined the Revolution and the founding of the new republic.

The Americans’ doctrine of “self-interest well understood” is not to be confused with selfishness, which is driven by one’s immediate if not base passions and desires, whereas the Americans’ “enlightened” self-interest is guided by reason and one’s long-term interests. The horizon of selfishness is narrow and right in front of one’s nose, whereas the horizon of self-interest is broad and far off. Though Tocqueville does not mention this specifically, he certainly implies that the “doctrine of self-interest well understood” is concerned with what is good or best for individuals in the context of the totality of their lives. Tocqueville’s understanding of “self-interest well understood” is a meaningful advance over past teachings on the nature and meaning of self-interest.

Rightly understood, self-interest American or Tocquevillian style also promotes the idea that men live in the context of a broader society from and through which all benefit by their association with others and the gains that come from trade material and spiritual. Tocqueville observed that Americans had developed a utilitarian philosophy whereby individuals pursued their own interests while also contributing to the wellbeing of others. For Tocqueville, a society of shared benevolence is one of voluntary giving and receiving, not as a zero-sum game of mutual sacrifice but rather as the common pursuit of a better life for all. In other words, reciprocal benevolence is in the self-interest of each individual, and it has the added benefit of advancing the overall happiness of the community. It is a philosophy of mutual trade for mutual advantage.

Thus, the Americans explain most of their daily actions, according to Tocqueville, through the doctrine of “self-interest well understood,” but he also notes that their “love of themselves constantly brings them to aid each other and disposes them willingly to sacrifice a part of their time and their wealth to the good of the state.” This is a good thing, according to Tocqueville; it’s how he justifies and rationalizes this new and controversial moral teaching. For the Frenchman, self-interest is “well understood” when an individual recognizes that their personal prosperity is linked to the wellbeing of their fellow citizens. This kind of “sacrifice” is for Tocqueville not the traditional sacrifice demanded by Christians or the kind of secular sacrifice demanded by socialists, but is rather a form of enlightened calculation that helps to promote a stable, wealthy, and benevolent society which, in the long run, benefits both the “sacrificing” individual and the community. In many ways, Tocqueville’s use of the word “sacrifice” dated him as still operating within the worldview of the ancien regime, but what Tocqueville was actually describing, but may not have had the language to describe, was something more akin to trading and benevolent sharing.

In the end, the Frenchman’s evaluation of “self-interest well understood” is that it “does not produce great devotion; but it suggests little sacrifices each day; by itself it cannot make a man virtuous; but it forms a multitude of citizens who are regulated, temperate, moderate, farsighted, masters of themselves; and if it does lead directly to virtue through the will, it brings them near to it insensibly through habits.” What Tocqueville observed in America is the existential coming-into-being of Benjamin Franklin’s new-model man—the man of the so-called bourgeois virtues—as described in his Autobiography. Tocqueville suggests that the proper doctrine of self-interest might very well come “to dominate the moral world entirely.” If this were to happen, Tocqueville predicted that “extraordinary virtues would without doubt be rarer,” but he also thought “gross depravity would then be less common.” All in all, the liberation of “self-interest well understood” would make the world a better, if less interesting, place.

In sum, Tocqueville supports the doctrine of self-interest well understood because it helps men to improve their individual lives and because it encourages them to help others even if only to serve their own ends ultimately. Tocqueville’s doctrine of self-interest well understood is then, in its least charitable interpretation, a kind of compromise position between the salutary benefits to be gained by liberating men to pursue their proper self-interest and the traditional moral teaching that requires of men that they sacrifice themselves for the sake of others.

Tocqueville’s view of self-interest represents one more step forward in the 300-year liberation of, and appreciation for, self-interest as a positive moral principle. The Frenchman’s primary contribution to this intellectual tradition was twofold: first, to distinguish between self-interest and selfishness and to elevate the former over the latter; and second, to treat self-interest as a virtue, though a virtue of at best middling status. There is nothing truly great in the doctrine of self-interest for Tocqueville, and so he cannot embrace it entirely as the highest moral good, but he does recognize that it “contains a great number of truths.” But whatever is true or good about the doctrine of “self-interest well understood,” he insists that it be enlightened and trained to ward off rank and subjective selfishness.

We might say of Tocqueville’s view of self-interest that he gives it two cheers rather than three.

Conclusion

Let us conclude with a gentle critique of Tocqueville’s doctrine of self-interest well understood. The Frenchman should be praised for seeing and praising the role of self-interest in human affairs, but his teaching is insufficient if not flawed in certain decisive respects. It represents a well-intentioned but fundamentally flawed attempt to reconcile the irreconcilable: self-interest and self-sacrifice.

For Tocqueville, enlightened self-interest does not mean, as it did for Aristotle, the rational and purposeful pursuit of one’s best life and the achievement of happiness; it does not mean holding one’s own wellbeing as the highest standard of moral purpose. Instead, like Adam Smith before him, self-interest is moral for Tocqueville primarily on social utilitarian grounds: it’s good because it encourages individuals to “sacrifice” for the sake of others as they pursue their own interests. Tocqueville seems to think that self-interest must be enlightened, tamed, disciplined, and channeled so that it can serve socially desirable outcomes.

In Tocqueville’s view, the individual’s interest is validated only insofar as it aligns with the interest of the group. In other words, Tocqueville has constructed a moral half-way house between selfishness and selflessness. To change the metaphor, the Frenchman is attempting to smuggle the moral philosophy of self-sacrifice through the back door of self-interest.

The problem with this position, is that it is unsustainable: it cannot withstand the weaponized guilt and the moral pressure of those who claim to speak either for the less fortunate or the common good. By suggesting that self-interest is only “well understood” and good when it serves the interests of others, Tocqueville implicitly accepts the traditional moral premise that service to others is the highest moral good and the standard of moral evaluation.

Tocqueville’s doctrine also perpetuates a false dichotomy between benevolence and acting in one’s self-interest. The reality of social life in a free society is that rational and moral individuals can and will find their genuine interests harmonizing naturally with those of others, not because they follow a moral teaching that requires them to sacrifice their interests, but because rational people benefit from association and cooperation with others.

In the end, Tocqueville’s understanding of self-interest represents two steps forward and one step backward in the philosophic and historical progress of the doctrine of self-interest rightly, properly, or well understood. We are getting closer to a true doctrine of self-interest rightly understood, but we have a few more hills to climb before we arrive at our destination.

AUDIO VERSION

**A reminder to readers: please know that I do not use footnotes or citations in my Substack essays. I do, however, attempt to identify the author of all quotations. All of the quotations and general references that I use are fully documented in my personal drafts, which will be made public on demand or when I publish these essays in book form.

Great food for thought. I just wish we lived in less than corrupt and narcissistic times. I do not blame the breakdown of America on our forefathers who through grit, survival and optimism created a government and society that worked well helping us advance through the Civil War and two World Wars. I blame the corruption and lack of cohesion on Global Marxism and narcissistic psychopathology this ideology needs to flourish. I blame the terroristic style strategies and the breakdown of moral and family using strategies needed to rule and control. We were blessed to live under the influence of men and women who could read, think, moralize and build. Who were willing to sacrifice their lives for a better future for others. The evil and corruption wrought by the thinking of one stupid, lazy and immoral man is mind numbing. The road to serfdom is paved by his ability to invert what he personally ultimately morally was bankrupt in; Innovation, hard work, creativity and building a prosperous future. The road to serfdom is paved by sloth and laziness. This was the only way Marx knew how to live and then justified it by tearing down a society that achieved what he was unable to achieve.

I so enjoy your work!

Rand argued that rational self-interest is a moral virtue. Unlike the claimed “immoral” consequence of self-interest – i.e., naked “selfishness,” where one becomes focused on whatever has become one’s immediate and “out-of-context” desires - desires divorced from rational guidance, the "horizon" of rational self-interest is broad and far off, while the horizon of “naked” selfishness is narrow and always right in front of one’s nose!

Rand also argued that “reason must be man’s only absolute.” When it becomes so, one’s horizon Is never just “in front of one’s nose,” but is found through their rational vision appearing along the far-off horizon. “Selfishness” becomes rationally understood and held in esteem because it becomes rationally exhibited, not emotionally driven. Part and parcel of this type of world view produces a natural benevolence, as it is understood that such rational “selfishness” is shared by others! It becomes an example of Rand’s “brotherhood of values.”