Adam Smith and the Great Leap Forward

Part 6 in a series . . .

As we saw in A Brief (Philosophic) History of Selfishness, late-Renaissance and early-Enlightenment philosophers and statesmen began a slow, sometimes tortured, reconsideration of what I have called “The Thrasymachian Challenge” or the problem of selfishness. They sought to claim some degree of respectability for a concept that had been treated with contempt for two millennia (Aristotle being the notable exception). The most these early-modern philosophers and statesmen could do was to treat the idea of self-interest as a necessary evil at worst and as a necessary vice at best. The pursuit of self-interest was treated, in other words, as a distasteful but sometimes necessary and useful element of human nature.

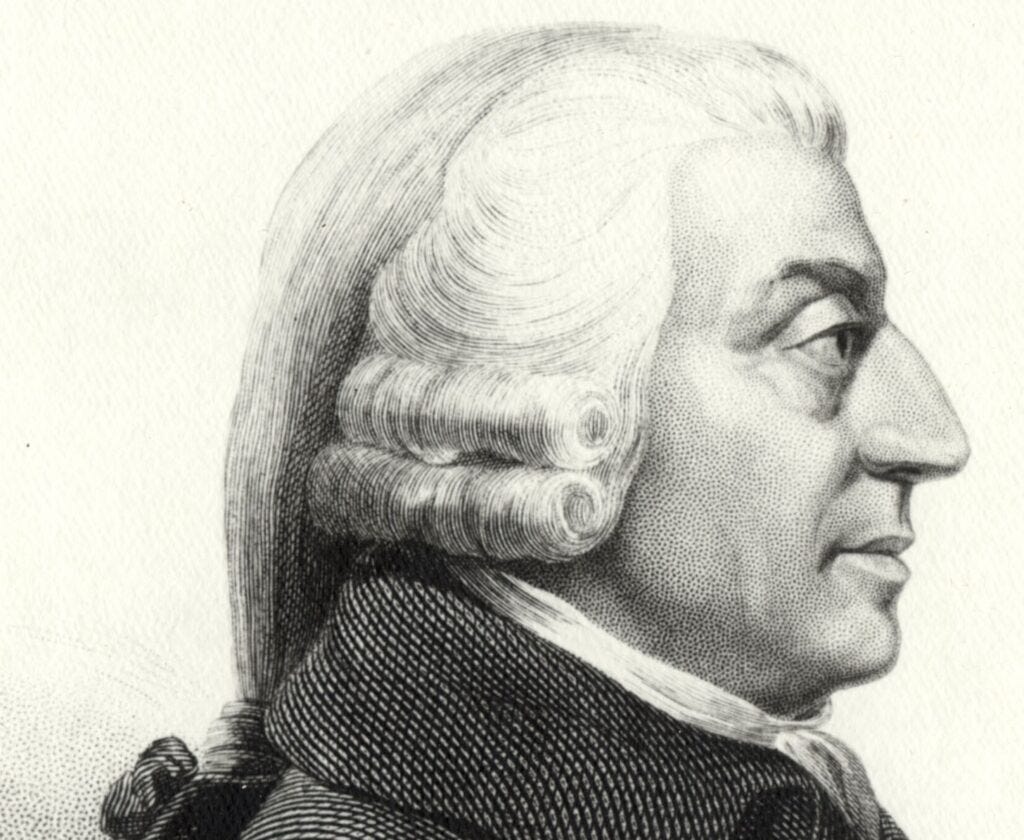

All of that began to change in the second half of the eighteenth century, when the Scottish moral philosopher and political economist, Adam Smith, reconceptualized the nature, meaning, and definition of the concept, “self-interest.” Smith’s great economic treatise, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), deployed the most powerful defense of self-interest written in the eighteenth century. There the Scottish professor presented a powerful economic justification for the pursuit of individual self-interest, and he also provided a partial moral defense of self-interest.

Self-Interest as Self-Improvement

Smith famously announced in the Wealth of Nations that all men are driven by a desire to better their condition, “which, though generally calm and dispassionate, comes with us from the womb, and never leaves us till we go into the grave.” Man’s desire to improve his life is best advanced, Smith argued, when he is left alone from meddling politicians. With new words to describe an old idea, Smith reconceptualized how men think about self-interest:

The natural effort of every individual to better his own condition, when suffered to exert itself with freedom and security, is so powerful a principle, that it is alone, and without any assistance, not only capable of carrying on the society to wealth and prosperity, but of surmounting a hundred impertinent obstructions with which the folly of human laws too often encumbers its operations.

Who could argue with the claim that it was natural, right, and good for man to “better his own condition”? Smith believed this “natural effort” of men to improve their “own condition” was wrought so deeply in man’s nature and was so powerful that it could overcome, at least to a certain degree, the misguided efforts of politicians to misalign human incentives. And in his great treatise on moral philosophy, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith claimed that the “great purpose of human life” was “bettering our condition.”

Smith’s simple turn of phrase—from selfishness or self-interest to “bettering our condition”—opened new psychic and moral possibilities for man.

In both the Wealth of Nations and his Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith declared that man’s “desire” or “effort” to “better his own condition” is both a descriptive fact of human nature (an “is”) and a moral imperative (an “ought” or the “great purpose of human life”). The Scottish philosopher also performed a masterful rhetorical move by referring to men acting in their self-interest not as selfish with all the associated negative connotations but simply as seeking to better their condition. Who could oppose that desire?

The fundamental postulate of Smith’s theory of moral action is that every individual is the best judge of his own interest (with exceptions of course), even though the “principles of common prudence do not always govern the conduct of every individual.” Smith’s position assumes that individuals act as a rule both selfishly and reasonably. The trick is to apply what Aristotle called “correct reason” to the pursuit one’s true and proper self-interest.

And with the self-interested desire to better one’s condition as a core requirement of human life, Smith went on to claim, in one of his best-known lines from the Wealth of Nations, that it “is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect or dinner,” he wrote,” but from their regard to their own self-interest,” which drives all human action. Such actions are, according to Smith, morally proper. Thus, Smith introduced a new way of thinking about the human condition that focused not on man’s “humanity” but on what he called his “self-love.” (The primary challenge for Smithians was and is to identify what he meant by “self-love” and whether the concept is legitimately connected to “self-interest.”)

We should recall here that Smith’s notion of “self-love” is reminiscent of Aristotle’s discussion of self-love in the Nicomachean Ethics, where the Athenian philosopher notes that the serious and good man is a “friend to himself, and so one ought to love oneself most.” The morally serious and noble man lives “in accord with reason,” and thus he differs from the man who lives “in accord with passion.” The properly selfish man “allots to himself the noblest things and the greatest goods,” and he “gratifies the most authoritative part of himself, and in all things he obeys this part.” He pursues what will “profit himself and benefit others” and does what he “ought to do” and “chooses what is best for himself.”

Smith also followed John Locke in thinking that it was a moral right and should therefore be a legally protected right for every individual in society to seek his own interest, particularly his economic interest, in his own way. Laws that violate that right, laws that interfere with market processes, are unjust, according to Smith, because they are “evident violations of natural liberty.” It is against the “interest of every society” (which means unwise) and morally wrong, Smith continued, for freely produced and freely exchanged goods and services to be “forced and obstructed.” Instead, the “law ought always to trust people with the care of their own interest, as in their local situations they must generally be able to judge better of it than the legislator can do.” Smith believed that every individual is the best judge of his own interests, which means he viewed government interference in production and trade to be a “manifest violation of the most sacred rights of mankind”—the right to improve one’s condition.

Self-Interest and the Natural System of Liberty

If Smith recognized the role individual self-interest in human affairs, what system or form of government did he propose to go along with it?

Smith and the other classical-liberal thinkers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries pursued policies of political economy founded on two assumptions: first, freedom from government intervention, and second, the natural harmony of interests. Smith’s political economy was grounded in the idea that the proper role of government in human affairs should be limited to protecting the lives and property of men and providing and enforcing common rules of justice. More precisely, man-made laws should not contradict the operation of the moral, social, political, and economic laws of nature, which, bear rewards if followed and punishments if not followed. Smith referred to this laissez-faire system of government that left men free to pursue their self-interest (both material and spiritual) as the “natural system of perfect liberty and justice” and “the plan of equality, liberty and justice.”

In sum, then, if individuals are, in most instances, the best judges of their own interests, and if all interests tend to harmonize spontaneously in a free society, then government intervention should be kept to a bare minimum. (Smith did, against his own logic and principles, support a limited form of government schooling and other “public goods.”) Smith argued in the Wealth of Nations that “All systems either of preference or of restraint, therefore, being taken away, the obvious and simple system of natural liberty” would establish “itself of its own accord.”

Thomas Carlyle, the nineteenth-century English essayist, once famously said of classical liberalism and Smithian political economy in his 1866 “Inaugural Lecture” at the University of Edinburgh that it combined “anarchy plus a constable,” which is not quite right. It’s not anarchy if there is a constable (even just one), and Smith’s system of natural liberty is best described as a system of order and harmony and not one of anarchy. Smith’s system is better characterized as “freedom plus a constable and a judge.”

That freedom and self-interest should lead to social harmony is one of Smith’s greatest insights. His best-known claim in the Wealth of Nations is that in a free society self-interested individuals will be “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of [their] intention.” The unintended consequence of everyone man pursuing his own self-interest is that “he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.”

Smith’s formula goes something like this: self-interest + freedom + general rules of justice = natural harmony of interests.

Smith viewed individuals as rational actors who pursue their self-interest and yet join with other men in mutually reinforcing and harmonious interests. The individual pursuit of self-interest leads invariably in Smith to production and trade, to a division of labor, to the operation of the law of supply and demand, to the work of the price mechanism, and then on to wealth production. Self-interest triggers and drives the whole system. Take, for instance, the law of supply and demand, which says:

The quantity of every commodity brought to market naturally suits itself to the effectual demand. It is the interest of all those who employ their land, labour, or stock, in bringing any commodity to market, that the quantity never should exceed the effectual demand; and it is the interest of all other people that it never should fall short of that demand.

When liberated from government intervention, the natural harmony or equipoise of interests that results when market processes are permitted to flow freely and find their natural course will “naturally lead them to divide and distribute the stock of every society, among all the different employments carried on in it, as nearly as possible in the proportion which is most agreeable to the interest of the whole society.”

The Scot’s laissez-faire theory of social organization assumed that self-interested individuals would form a natural identity and spontaneous harmony of interests if left alone. Smith’s invisible hand is a metaphor for the organizing mechanism that aligns different and sometimes competing individual interests (without their intention to do so) in a self-regulating system of social coordination and wellbeing.

This system is the result of what might be called a natural identity and fusion of interests between individuals. Smith and many other classical liberals of the time believed that if men were left free to pursue and trade their self-interested values under a general operating system of justice, their actions would harmonize naturally and produce spontaneously the wellbeing of the society. In other words, Smith claimed that there was a natural identity of interests between self-interested individuals that grows out of the coordinating effects of the division of labor, supply and demand, the price mechanism, competition, and trade. The natural identity of interests can only occur if individuals are left alone and free to pursue their selfish interests. Government intervention in the economy disrupts market relations in two ways: first, it disrupts the naturally occurring allocation mechanisms of the market; and second, it suppresses individual initiative.

When Men’s Interests Conflict

This is not to say, however, that Smith did not understand that men’s interests sometimes conflict. This happens all the time, and there are innumerable reasons why men’s interests sometimes conflict. Sometimes men—including rational and honest men—have competing or opposing interests. Competition is one of the features of a market economy, which is resolved in a rational and just way by a third party, namely, the customer. Sometimes the interests of irrational men conflict with those of rational men. Sometimes men—including mostly rational men—follow their urges, feelings, whims, desires, passions, emotions, and prejudices rather than their rationally calculated interests as defined by a particular good that objectively enhances one’s general good. Sometimes men come into conflict because they have incomplete information, or they err in their calculations. This happens because man is neither infallible nor omniscient. Sometimes there are miscommunications between two or more men. This is particularly true when two or more men are called upon to rely on their faulty memories of agreements made in the past. Finally, sometimes men are poor judges when it comes to evaluating and judging their own ideas, interests, and actions. The distance between self-interest and self-deceit is too close for comfort. In other words, sometimes men are too partial to their own interests, and sometimes that partiality leads to injustice.

The most common source of conflict between men occurs when one man, a few men, or many men attempt to define or impose their vision of what is good on other people (what Smith sometimes call the “spirit of system”), particularly when they use individual coercion or the coercive force of the State to achieve their vision of the so-called “common good.” Smith found that men who claim to speak or act for the so-called “public good” rarely do so or achieve their end. Instead, they cause turmoil and division as they attempt to impose their vision of the common good on everyone else.

The man of system . . . is apt to be very wise in his own conceit, and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it: he seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board; he does not consider that the pieces upon the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might choose to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder.

The common good for Smith is not and probably should not be the primary object of politicians but some kind of general good can nevertheless be achieved as a kind of spontaneous result of independent, self-interested individuals acting for their own benefit within a system of common freedom and justice, which is all that is necessary to achieve the “common good.” What Smith has done is to reconcile individual good with the common good, or at least this is what he thought he was doing.

Self-Interest and Justice

In addition to freedom, the Smithian pursuit of rational self-improvement requires what might be called a general operating system (i.e., a moral-legal framework) to run self-interest through channels that simultaneously decrease conflict and increase harmonious and mutually beneficial interactions between individuals. (Smith compares this general operating system to the “rules of grammar” and the rules of “composition.”)

According to Smith, “All the members of human society stand in need of each others assistance, and are likewise exposed to mutual injuries.” This is the core fact of human society. The natural bonds of affection are a necessary condition for a well-functioning free society, but they are insufficient. Something else is needed. The truth of the matter is that every society will have individuals within it “who are at all times ready to hurt and injure one another” and once that happens the bands of society “are broke asunder.” To correct this inherent problem, a general system of conduct, virtue, and justice must be established to provide men with guidelines, boundaries, and incentives. “Justice,” Smith says, “is the main pillar that upholds the whole edifice,” and without which the whole network of associations must “crumble into atoms,” and the “general rules of conduct” help to correct the “misrepresentations of self-love.” Nothing less than the “very existence of human society” depends on the existence of these rules. The result of combining a system of freedom and justice is nothing less than the spontaneous generation of a natural social order that “appears like a great, an immense machine, whose regular and harmonious movements produce a thousand agreeable effects.”

Conclusion

Smith’s way of viewing the world and man’s place in it upset several thousand years of human reflection on the nature and meaning of selfishness and self-interest. For the first time in Western civilization, the idea of self-interest was not simply viewed as a vice or a sin. At the very least, self-interest was seen as an observable if not a necessary fact of human nature. At most, some Enlightenment-era thinkers were coming to view self-interest as the starting point or as a necessary condition of moral thought and action.

In the end, Smith’s theory of political economy represents at genuine leap forward in how men came to view the nature and role of self-interest or even selfishness in human life, but it is also true to note that he does not quite go the whole way. Smith’s moral justification for the role played by self-interest in human affairs was largely pragmatic and utilitarian. He still viewed the individual pursuit of one’s self-interest as somehow morally unbecoming or tainted. The pursuit of individual self-interest was morally acceptable if not good primarily because it served the common good as the end. This means that Smith takes the common good rather than the moral rights of the individual as his standard of moral value. This idea has, more than any other, retarded man’s moral development. Smith came closer to approaching the moral Mecca than any other philosopher hitherto, but he did not quite reach the promised land.

I am making the audio file available to everyone this week.

**A reminder to readers: please know that I do not use footnotes or citations in my Substack essays. I do, however, attempt to identify the author of all quotations. All of the quotations and general references that I use are fully documented in my personal drafts, which will be made public on demand or when I publish these essays in book form.

Please put the fact that your essay can be listened to at the beginning, not at the end...where it will be seen after reading all of it.

I’m eager to read your entire essay. I hope you have recovered fully.